East Africa offers considerable potential for transport infrastructure expansion and investment - Shem Oirere reports

Infrastructure, infrastructure and more infrastructure is what is needed to make East Africa the favoured destination and Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda have unveiled grand plans to enhance the infrastructure both nationally and regionally.” This is how market analyst

This is the same message transport infrastructure experts, who converged in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania for the 5th East and Central Roads and Rail Infrastructure Summit on August 26th and 27th, echoed as they dissected existing investment potential and challenges in East and Central Africa's two main transport corridors of Northern and Central.

“There is some sort of vicious circle in many African countries where lack of public investment in the transport sector leads to lack of economic growth, low levels of unemployment and therefore little or no earning and subsequently high levels of poverty,” said Eric Kaleja director, German Investment Corporation.

He said Sub Saharan Africa needs US$93 billion/year for infrastructure development, which can only be realised “through embracing the private sector as long-term partners.”

“Africa needs good transport links to stimulate economic growth and create job opportunities but the sector faces many challenges such as insufficient investment which calls for an increased role of the private sector,” said Maggie Tan, chief executive officer of the Singapore-based

“Many people in East and Central Africa do not have access to reliable good transport infrastructure with students and teachers having to cross dangerous streams and rivers to reach school, while women are forced to give birth at home because they cannot make it to public health institutions because of the poor state of the roads in the region,” she said.

In addition, East and Central Africa is one region with “high transport costs and poor intermodal linkages,” according to Patrick Tamba Musa, senior transport engineer, Africa Development Bank (AfDB).

“It costs an estimated $2 cents to transport a tonne of cargo/kilometre in the USA compared to $10 cents or more in many African countries. This hampers economic growth,” he said.

However, despite the transport infrastructure challenges in East and Central Africa, the recent discovery of huge oil and gas reserves in the region and ongoing efforts to increase intra-regional trade, through the strengthening of the East Africa Community (EAC) regional trading bloc, have attracted the attention of private investors and international lenders, triggering a higher demand for efficient and sustainable transport systems.

“Mineral, oil & gas discoveries in the region present anchor products that attracts private sector investment,” said Joster Onyango, Railways Technical Advisor at the EAC, a regional trading bloc bringing together Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi.

He listed several road and rail projects in the region, which provide investors an opportunity to grow both their market share in the region and investment earnings.

For example, construction of the 260km Arusha-Holili-Voi Road is in the final design stage while the 400km Malindi-LungaLunga and Tanga-Bagamoyo Road has received $5.5 million grant of resources from AfDB for project preparation, opening an investment window for the private sector.

Construction of the 92km Lusahanga-Rusumo Road is also up for grabs after AfDB approved funds for its detailed design and that of the 70km Kayonza-Kigali Road, both linking Tanzania and Rwanda.

In addition, the stage is now set for the detailed design for the 250km Nyakanazi-Kasulu-Manyovu Road and 78km Rumonge-Rutunga-Bujumbura Road, which connect Tanzania and Burundi.

Tanzania transport permanent secretary Dr Shabaan Mwinjaka, who gave the key-note address at the summit, said the country plans to upgrade over 600km of trunk road to bitumen standard, rehabilitate another 193.5km to bitumen standard and upgrade 59.25km of regional roads to bitumen standard in addition to the rehabilitation of 424.5km to gravel standard.

Other regional projects, which may have been contracted but could still hold potential for management concession opportunities include the $466 million Nairobi Northern Bypass, currently under construction by China Road and Bridge Corporation and the 39km Eastern road bypass also in the Kenyan capital.

Tanzania and Rwanda are also constructing the new Rusumo Bridge and One Stop Border Post (OSBP) facilities under a contract by Japan’s Daiho Corporation Company.

Plans for East Africa’s first toll highway linking Tanzania’s capital Dar es Salaam to the city of Morogogo, a distance of 200km, is one of the projects whose investment potential was promoted at the Dar es Salaam summit despite some reservations by private sector participants and financiers over the lack of proper linkages of the region's international trunk roads and rail network.

However, EAC countries, through their secretariat in Arusha Tanzania, are working on the creation of a seamless international trunk road system in the region and standardising the management of the Northern and Central corridors.

For example, Onyango said the countries are at the moment fine-tuning policies that would enhance movement of cargo and passengers while at the same time maintaining high quality roads. He gave the example of standardising the width of the region's international trunk roads, which now range from 6-7m on single carriageway. The countries, through EAC, have agreed to have the width of all these roads at 7m plus 2m shoulders in tandem with international practice.

Onyango also called for an efficient intermodal transport system, coordinated from one transit operation and control centre, even if road and rail modes of transport are operated by different public or private agencies.

“There is tremendous growth in Intra-regional trade, which provides great impetus for expanding the intermodal and economic infrastructure,” he said.

Currently, Onyango said, transhipping of cargo faces serious challenges because of the lack of a common coordination centre that monitors operations at the intermodal terminals such as seaports or in-land terminals such as the railyards.

Despite Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda allocating a combined $3.7 billion for road and rail infrastructure, out of their $39.84 billion combined budget for 2014/15, no funds were specifically set aside for installation of intelligent transportation systems to manage the respective countries’ incomplete intermodal integration both along the Northern and Central corridors.

The Northern Corridor, the busiest transport route in the region, links the landlocked economies of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and Eastern DR Congo to the port of Mombasa in Kenya while the Central Corridor is anchored by the port of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania linking to the road and rail networks to these landlocked countries.

Except for investment in additional general purpose lanes on highways and an attempt by Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda to establish high occupancy lanes, the governments are yet to tap into the potential of corridor management systems such as loop detectors to help both public and private players collect accurate truck and locomotive movement data, closed circuit televisions (CCTVs)—except for about two in Kenya— to monitor traffic along the two corridors or even adequate functional ramp meters, which are critical in the coordination of any effective intermodal transportation.

Investing in high impact technology and formulation of coordination strategies on the intermodal transportation networks in East Africa was singled out during the Dar es Salaam summit as an opportunity for private sector investors.

Currently, cargo is offloaded at either Mombasa port in Kenya or Dar es Salaam port in Tanzania before it is transported by trucks to the Kenya/Uganda rail yard in Mombasa or Central Tanzania railyard in Dar es Salaam. It is then packed into a train for dispatch to another railyard where the rail connects with the international trunk road such as the Mombasa/Nairobi highway in Kenya. Trucks are then used to transport the cargo from these railyards to the rest of the region.

The infrastructure experts called for coordination of the intermodal transportation regime by having the seaports, rail and road operations coordinated by one common agency, unlike now when each of these modes of transport are managed by different government agencies with different operational standards, which experts now want to put under one central command for efficiency.

“As it is now in East Africa, there is no body coordinating the intermodal transport system which leaves the burden to the customer to coordinate the function and ensure the cargo arrives at its destination,” said Mahamud Mabuyu, National Logistics Officer, World Food Programme in Tanzania.

“To achieve reduction in transit time, the region needs to work on standardising the rail gauge and road management because currently operations of key players such as customs agencies, port authorities and transport companies are not integrated.”

However, Tanzania was cited as one of the countries that is currently working at unlocking its Central Corridor through a three-prong approach, according to Dr Mwinjaka.

First, the government intends to increase the efficiency of the port of Dar es Salaam to boost its throughput from the current 12 million tonnes to 18 million tonnes by 2015/16 through investing more public funds in purchasing modern port equipment and building personnel capacity on modern seaport operations.

Secondly, the country hopes to increase cargo moved by rail within the corridor from the current 200,000 tons to three million tons by 2015/16 by rehabilitating the railway line tracks, purchasing rolling stock and remanufacturing locomotives and wagons at the Tanzania Railway Corporation’s plant at Morogoro. And, finally, the plan hopes to reduce travel time by trucks from the Dar es Salaam port to neighbouring Burundi and Rwanda from the current three and half days to two and half days by the end of 2016 by reducing weighbridges and introducing an electronic trucking system.

The plan’s success, however, will depend on how soon, and committed, countries in the region would be in the implementation of proposals to standardise the region's road maintenance regime, whose absence hampers trucking business.

For example the design of the regional roads and maximum axle limits are still a major challenge to the region’s two transport corridors.

But recently the EAC member States announced progress in plans for a policy that would require them to ensure an International Roughness Index (IRI), or measure of road roughness quality, of between five and six. Road agencies in the region can determine the quality by using the latest version of the Highway Development and Management Model (HDM), which has been described as a primary tool for analysing, planning, management and appraisal of road maintenance, improvements and investment decisions, distributed by HDMGlobal.

The countries have also agreed to ensure that pavements with cracks should be repaired within 90 days after their appearance, especially on international trunk roads linking them.

Loaded trucks in East Africa should be limited to a speed of 65km/h while empty ones should move at 80km/h under the agreed operational regulations.

In addition, the countries have agreed to ensure that major cities such as Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, Kampala, Kigali and Bujumbura are bypassed when truck traffic reaches 1,500 vehicles/day, with a parking or rest area for buses, cars and trucks arranged at least every 250km.

The Federation of East Africa Freight Forwarders Associations president Merian Sebunya Kyomugisha said road maintenance in East Africa should not be addressed in isolation but together with the contentious issue of the acceptable maximum on axle loads and Gross Vehicle Mass (GVM).

“If we maintain our roads in good condition, it means they will be passable and movement of our cargo from the seaports will be efficient because of the improved turnaround time,” she said.

However, she said the private sector, especially those in the trucking business, must support East African governments in enforcing the axle load rules to arrest the rapid deterioration road infrastructure.

“Truck operators and owners should be told in no uncertain terms that if they destroy the roads today by overloading, the roads will destroy their vehicle tomorrow and they will be out of business,” said Kyomugisha, who is also the managing director of BTS Clearing and Forwarding.

Her position has been supported by the chief executive officer of the Kenya Association of Manufacturers Betty Maina, who said previously: “Overloading normally leads to rutting and cracking among other deformations of our roads, which shorten the pavement design life resulting in increased vehicle operating costs, reduction in service levels, unsafe conditions leading to increased accident risks and increase road maintenance costs.”

She said poor conditions of roads in East Africa are a major cause of “road carnage and high transportation costs which transporters pass on to cargo owners – mainly manufacturers who import raw materials.”

“For importers, inland transportation, handling and document preparation constitute the bulk of transport costs which stand at US$400 for terminal handling, $800/20-foot container, and US$600 for document preparation - all totalling to $1,800.”

Kenya recently passed the Kenya Road Act 2007 and Traffic Act which stipulates that a commercial vehicle must fall within the statutory gross weight of 48tonnes and that each of its axles must not exceed 8tonnes. The regulation has been suspended by the High Court after truckers petitioned the “per axle” requirement.

In Early August the World Bank, Kenya Transporters Association and the Northern Corridor Transit and Transport Coordination Authority (NCTTCA), a regional body, jointly came up with a self-regulatory charter to curb overloading on East African roads after surveys indicated compliance with axle load limits in the region was less than 75%.

NCTTA says: “The self-regulatory charter is anchored in the East African Community Vehicle Load Control Bill 2013, which provides a framework to be applied within the region.”

Under the EAC Load Control Bill of 2013, the gross vehicle weight has been harmonised to 56tonnes with the maximum for each axle limited to 10tonnes. This is yet to be fully implemented with Uganda, Burundi and Rwanda still allowing a maximum of 52tonnes, Tanzania 56tonnes and Kenya 48tonnes.

Elsewhere, the anticipated road and rail construction boom in East Africa is expected to increase demand for bitumen or asphalt cement supply according to Gratian B Nshekanabo, managing director Starpeco Limited in Dar es Salaam.

Nshekanabo, who gave a presentation on bitumen demand and supply in East and Central Africa, cited the example of Tanzania, where he said in a single financial year the government constructs an average 800km of roads to bitumen standard, consuming an estimated 12,000 million metric tonnes of bitumen annually.

An estimated 1,023.4km of roads or 17.25% of the

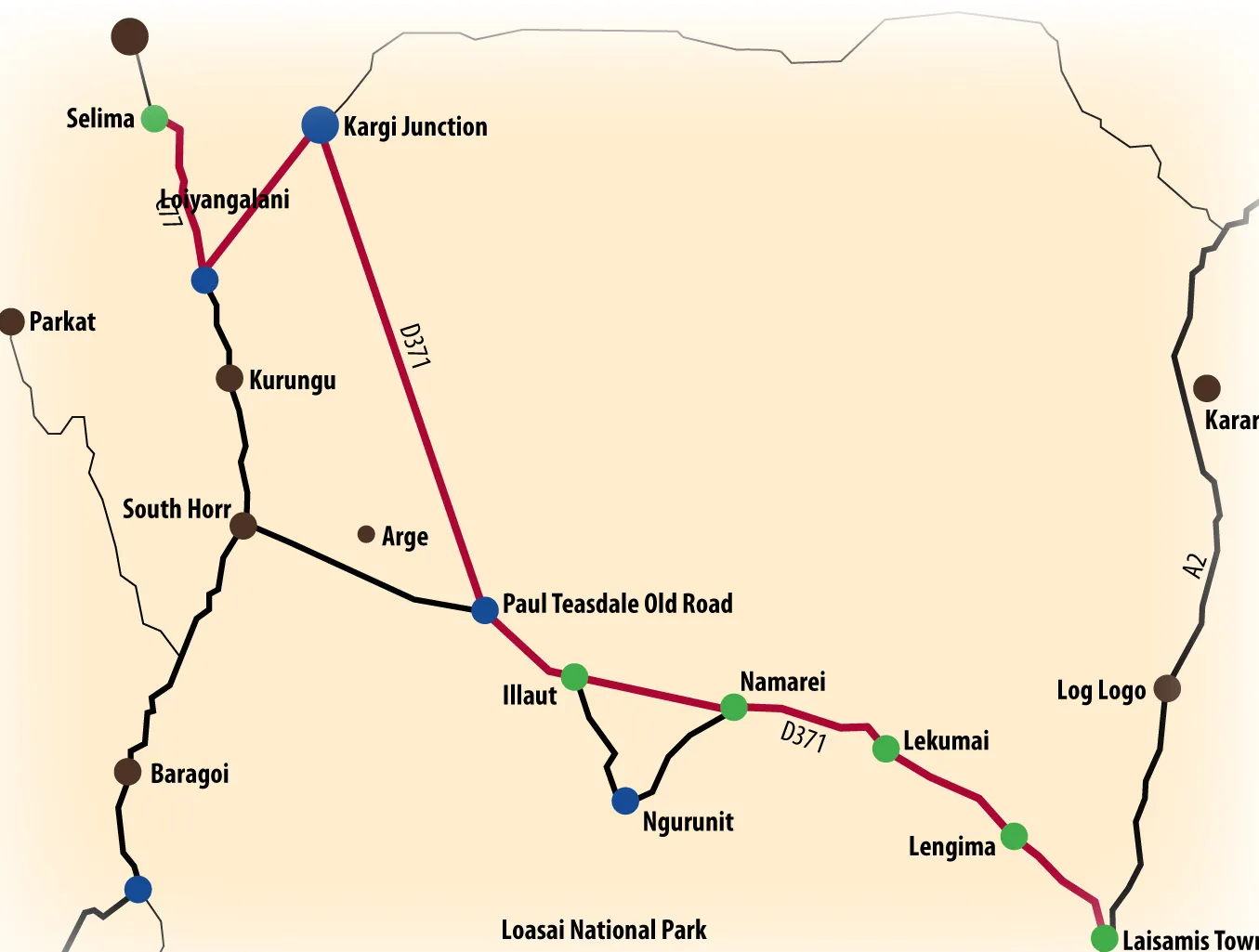

Northern Corridor’s 2,038km are said to be under rehabilitation or reconstruction in the region, opening yet another opportunity for investors keen on venturing into East Africa's bitumen market.

“Bitumen demand in East Africa, which currently is estimated at 100,000 million tonnes/year, will mainly be driven by road development in the region,” said Nshekanabo.

He said because of the varied nature of the region’s topography and land surface, all types of bitumen such as primer, penetration grades and modified bitumen have a ready market.

Currently, the market demand is met by supplies from United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Singapore after the former market leader, Iran, was edged out because of the international economic sanctions over its nuclear development programme.

Nshekanabo said opportunities in bitumen investment in Eastern Africa include creation of bonded storage reserves in the coastal areas especially at the Dar es Salaam and Mombasa ports, investing and promoting emulsion bitumen products and bitumen container business, leasing and hiring of bitumen processing and discharge and finally trading and popularising bitumen packed polycubes and polybags.

However, funding of road and rail systems in East and Central Africa remains a major hurdle in achieving infrastructure targets in the region.

Kyomugisha called for the introduction of an infrastructure development levy at the Mombasa and Dar es Salaam ports to mobilise funds for road and rail construction and maintenance.

“This should be a levy specifically for transport infrastructure development and should not end up in the government consolidated fund where it can easily be diverted to other emergencies,” she said.

Kenya introduced a railway development levy, which will support the construction of the 609km high speed single gauge standard railway line linking the port of Mombasa to the capital Nairobi at a cost of $3.6 billion. The levy is funded by a 1.5% tax on all Kenya-bound imports in the last half of 2013, the government collected $112 million of the levy surpassing the $76 million target for the period.

“The private sector, and especially the importers and exporters would not mind paying a little more in infrastructure development levy if they can be assured the funds will be held in a separate account and used in construction and maintenance of our roads and rail infrastructure,” said Kyomugisha.

Senior Transport specialist at the World Bank, Yonas Mchomvu, said there is room for public private partnership in the development and management of road and rail in East Africa but the model's success will depend on willingness by governments in the region to embrace several practical steps towards better infrastructure development.

He urged Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and DRC to “provide investors with a clear, stable and conducive regulatory framework to invest with reasonable return and to carefully scrutinise investment to ensure there is a solid business case.”

In addition to strong transport sector regulations, Mchomvu said concessioning of the modes of transport such as rail and road, “is not always a panacea to transportation challenges but public private partnerships can work best where there is a progressive transport strategy and governments and private sector appreciate the fact that investing in infrastructure requires long term guarantees and strong institutional frameworks.”

He urged governments in East Africa to give priority “to the rehabilitation or refurbishment of the existing network before constructing new” because any investment in transport infrastructure by the private sector or international lenders “must be justified by a solid business case, which is the level of financial sustainability and rational for public sector subsidies.”

“The business case for railway depends on the improvement of train availability, reliability, punctuality, and financial sustainability, not on size of track gauge,” said Mchomvu.

And as Tan concluded “there are opportunities in East and Central Africa for building safer, cleaner and more affordable transport systems that will solve the congestion problems, create access to markets and help tame climate change by lowering emissions levels.”